This is Circl, a new pavilion in Amsterdam's Zuidas district. A place created by ABN AMRO where it can share the knowledge it has gained about circularity and advise its clients effectively about that issue. A building designed and constructed according to sustainable and circular principles. Circl has been created to be energy efficient and easy to disassemble, to make as little impact as possible on the planet. Many of the things used to build Circl have already had a previous life. Other raw materials – from the wood used in its construction to the aluminium on its outer walls – can be put to new uses in the future. What’s more, Circl is a living lab - a place where anyone and everyone with good ideas about sustainability and circularity can find the space they need.

Circl is a place to learn, to gain inspiration, but above all to bring people together. But how and why did ABN AMRO come to build this exceptional pavilion?

This is a story of dreams, ambitions and the power of advancing knowledge and ideas.

Prologue

It was the summer of 2015. Hans de Jong hesitated a moment before hitting the ‘send’ button. His e-mail was short, simple and unambiguous. Its consequences, however, were going to be enormous. A lot of people were going to get angry; some might even start to panic. Plans were going to be thrown into chaos. Budgets missed. Investments written off. There was a lot of money involved, and some major interests at stake.

But De Jong and the three people backing him at ABN AMRO were sure this had to be handled differently. Construction of the new pavilion just outside the bank’s head office in Amsterdam's Zuidas district had to be stopped – and it had to be stopped immediately. No matter that the plans had got official approval from the Managing Board. No matter that the ground had already been excavated and that everyone at head office was desperate for more space - this particular train had to be brought to a halt without delay.

De Jong took a deep breath and pressed the button. The e-mail was addressed to practically everyone involved in the project: the architect, construction company BAM, the facility managers at ABN AMRO – all of them would soon be reading a few short lines, telling them that the bank had decided to stop the construction work completely.

Hans de Jong then turned off his computer and phone. It was time to let that message do its work.

The square and the plans

The final element in the 'Berlage axis'

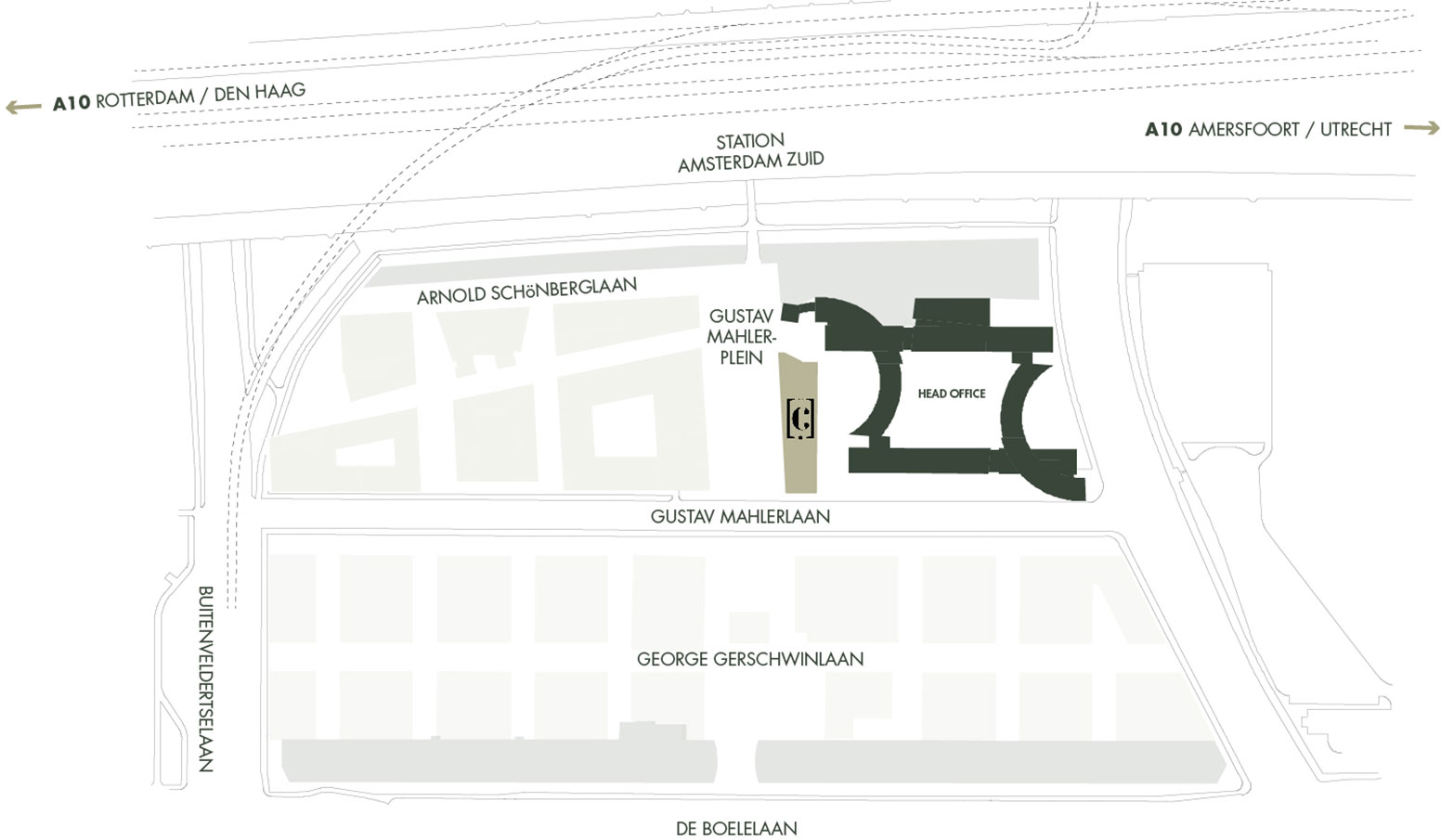

There had been vague plans to build a pavilion on the square alongside Amsterdam’s Gustav Mahlerlaan since ABN AMRO built its head office there in 1999. The bank was one of the first to take up ‘residence’ in the part of Amsterdam known as the Zuidas (literally, southern axis), a new business district with international appeal, which was then in development. It offered excellent rail, motorway and airport connections, while still being close to Amsterdam's historic centre.

In those early years, the bank had indeed agreed with the Amsterdam City Council and architect Pi de Bruijn of de Architekten Cie, the Dutch partners of the American designer of ABN AMRO’s head office, that ABN AMRO would build a pavilion in front of its headquarters. De Bruijn had been involved in the development of the Zuidas since the early 1990s and was eager to work together with the city council to turn the planned office district into a great place to live and visit. This ABN AMRO pavilion was going to be a meeting place - not only for people who work in the offices in Zuidas but for the entire neighbourhood - with a range of facilities like a bar, restaurant and conference rooms. De Bruijn saw this pavilion as the final element in what is known as the ‘Berlage axis’ (after the Dutch architect H.P. Berlage), which cuts straight through the Amsterdam-Zuid district and connects the city centre with the Zuidas.

Building site

But in the early years following ABN AMRO’s move to the area, Amsterdam’s new business district remained one enormous building site, where little or nothing happened at all after 6 p.m. It didn't appear to be the kind of the place where you would want to build a meeting place with conference rooms and a restaurant. Furthermore, as the bank saw it, a pavilion didn't seem to be a particularly attractive real-estate investment. It was going to cost a lot of money, yet yield relatively little in return. Nonetheless, in 2008 it was decided that the Zuidas needed further development.

No barrier

The original plans for the Zuidas envisaged that the A10 ring road and the railway lines close to Amsterdam-Zuid railway station would run underground. In this way, there would be no physical barrier between the leafy residential areas of Amsterdam-Zuid and the new business district. For practical and financial reasons these plans never materialised. But in 2010 the Amsterdam City Council and the Dutch Ministry of Public Works started making new plans, part of the 'Zuidas dock' project, to move the motorway underground after all.

Another - and, for ABN AMRO, more significant - development was the plan to increase the capacity of Amsterdam-Zuid railway station as it was unable to cope with the growing number of passengers. Besides larger and wider platforms, the station was also to have large bicycle parking facilities underneath it, with direct access to the square in front of ABN AMRO’s head office. At that time, the square itself was rather dull. Some 80 percent of it was surfaced over, taxis drove visitors to the bank and away again, there were some plant containers and a few scattered trees, and that was it. Part of the head office's underground car park was located beneath it.

The right time

The bank wondered whether, with Amsterdam-Zuid station about to be expanded, this might be a good time to do something about that square as well. So, in 2013, acting on the instructions of Chief Operating Officer Johan van Hall, two members of staff at ABN AMRO got to work on the project: Dick Lussing, then Facility Services Manager, and Hans de Jong, who had already worked as senior project manager for the bank for more than 20 years.

The two men put together a team that included technical advisors, ABN AMRO real estate specialists and de Architekten Cie, which - as co-designer of the head office - was required to guarantee that the look and feel of the square and the office complemented one another. Together they drew up plans for a new garden, with a few small restaurants or pavilions scattered about, somewhat in the style of New York City’s Central Park.

The bank thought this might be a good time to do something about the square

During that process, a practical problem also presented itself: the head office was bursting at the seams. The building, erected in 1999, originally provided space for 3,200 staff, but now, on busy days, as many as 6,000 people would be working at the Gustav Mahlerlaan offices. When ABN AMRO staff wanted to hold a meeting of, say, 20 people it was almost always necessary to find a location outside the head office. That was costing the bank a lot of money.

Flourishing

It was then that the original plan for a single pavilion resurfaced – a place for the bank to receive guests, host events and hold meetings. In the meantime, the Zuidas district had also started to flourish, with more cafes, bars and restaurants, more business activity in general and thousands of new homes, either already built or in the pipeline.

De Architekten Cie also still had a desire to complete the work on the 'Berlage axis'. Every year, Pi de Bruijn would write in his Christmas message to the bank's board of directors, "Shall we do something about that pavilion?" The city council was also keen on the idea. Cie suggested digging up part of Gustav Mahlerplein to create space - between the new underground bike park at Amsterdam-Zuid station and ABN AMRO’s head-office underground car park - for a large underground meeting place with a smart-looking bank pavilion on the square above.

It sounded good to Johan van Hall and he set people to work on the figures.

A 'typical' building for a bank

Rob Kuipers' official title is something of a mouthful: Product-Contract Manager Maintenance - the person responsible for maintaining a large part of the bank’s corporate offices. Within ABN AMRO he has a reputation for being something of a sustainability guru. Anyone who wants to know something about making buildings more sustainable, about energy-neutral housing or work, or about minimising waste flows soon finds their way to Kuipers (he is, incidentally, also the man who takes care of the family of peregrine falcons - a species of birds of prey threatened with extinction - who have been living on the roof of ABN AMRO’s head office since 2013).

At the end of 2014, Hans de Jong brought Kuipers into the team that was working on the construction of the pavilion. By that time the figures had been approved. De Jong also got two younger members of ABN AMRO’s staff involved in the pavilion team: project manager Rudolf Scholtens and Malu Hilverink, who would eventually be more involved in what the building would ultimately be used for.

Stone for the walls

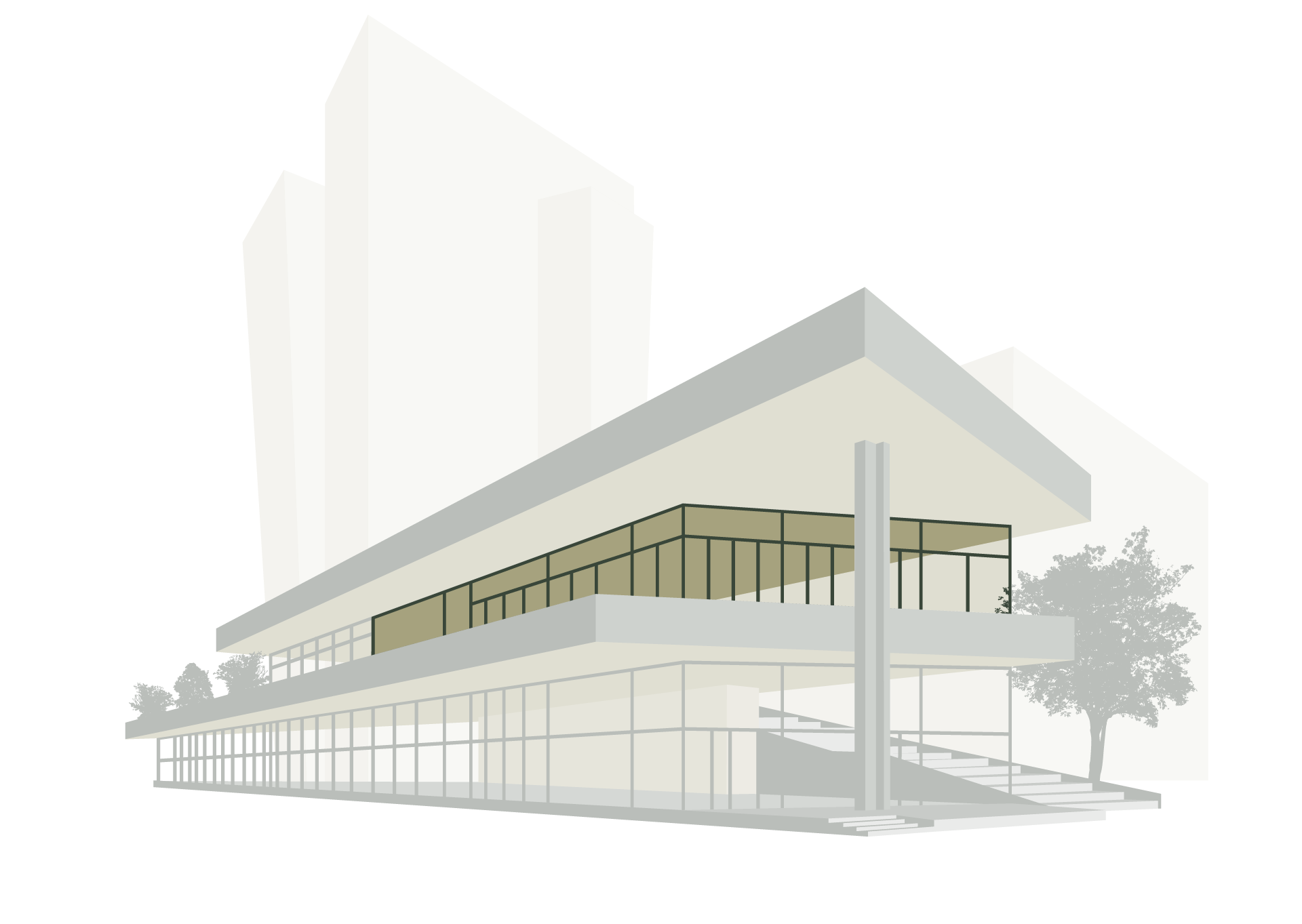

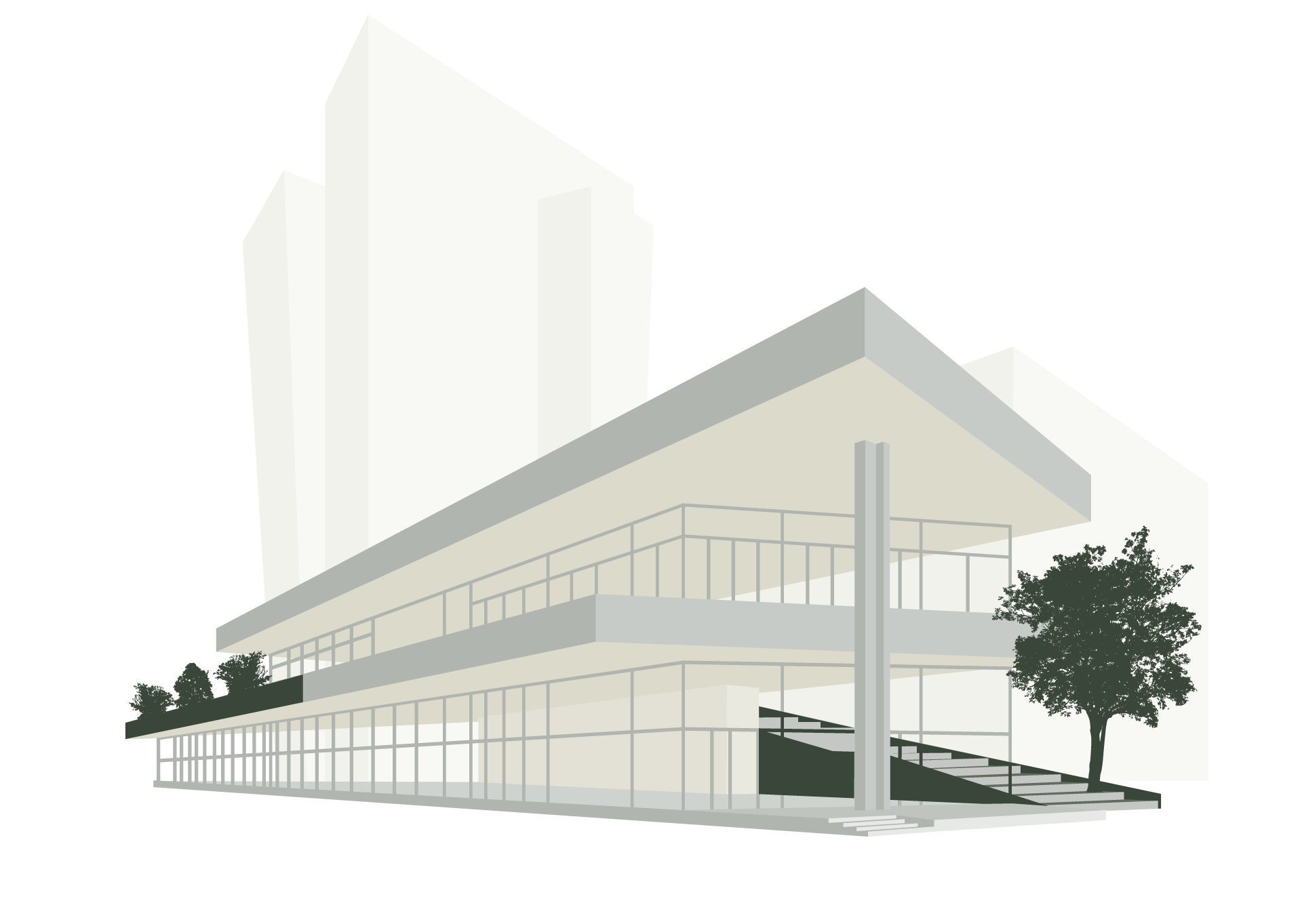

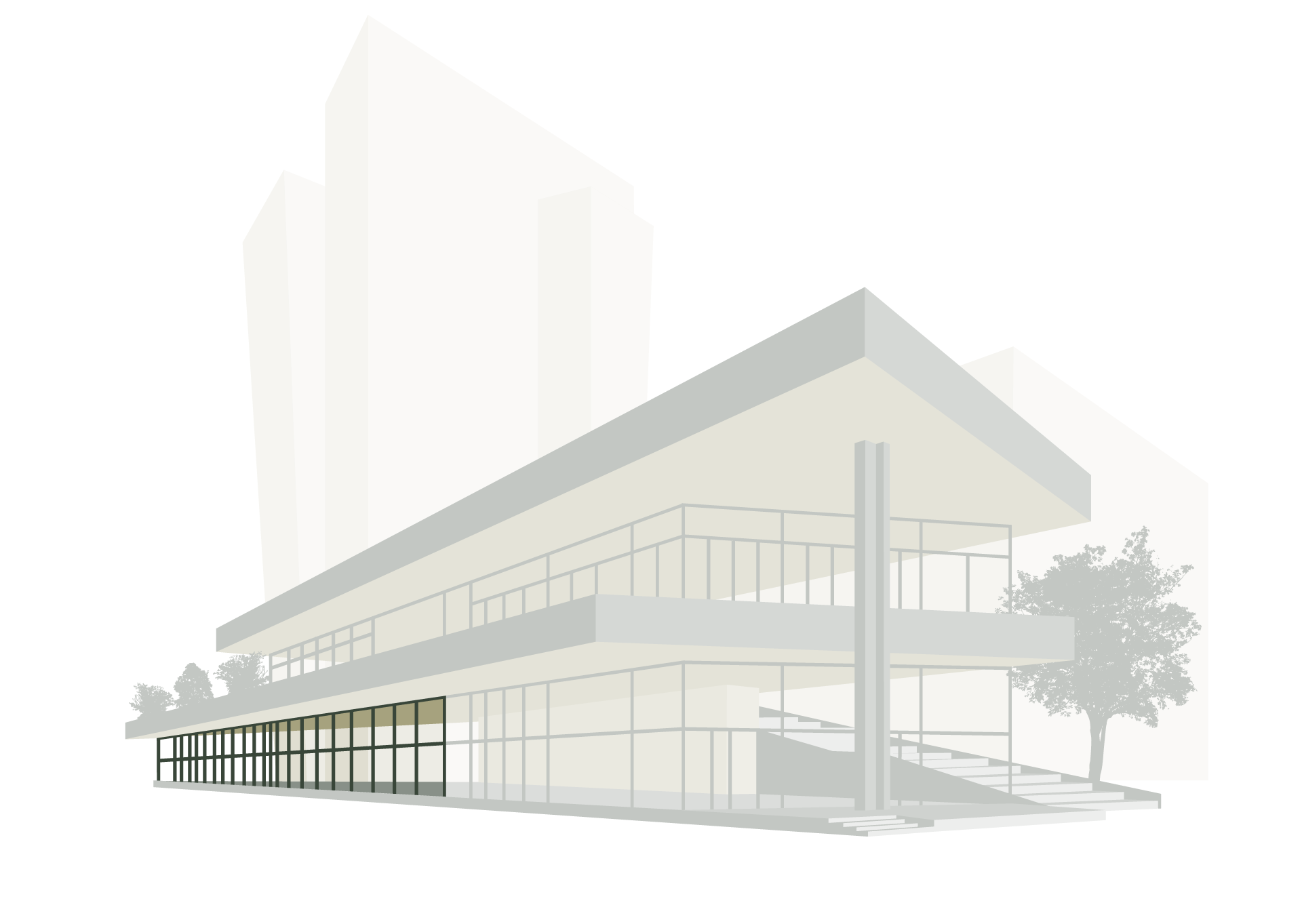

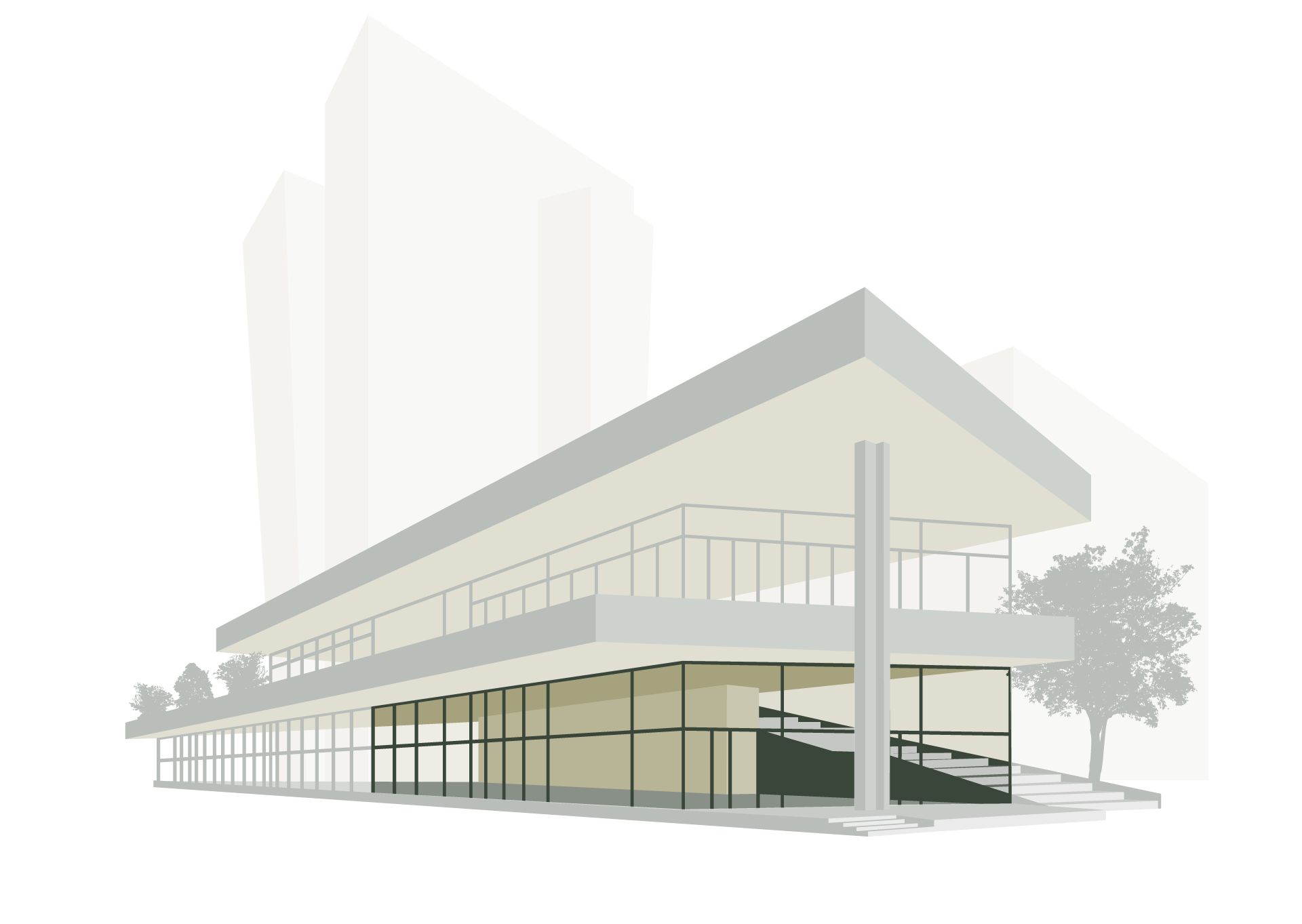

At this time, construction company BAM Infra was already working on creating the bicycle storage areas under Amsterdam-Zuid station and was just about ready to start digging an enormous hole right in front of ABN AMRO’s head office. In the boardroom at the top of the building a small row of different types of stone had been put together so that the board could choose one for the pavilion's external walls. Hans Hammink, one of the chief architects at de Architekten Cie, had come up with a beautiful design for a classic, largely concrete, oblong-shaped pavilion. It had the look and feel of a typical building owned by a bank. The interior would feature a lot of white stucco, stone and marble.

The basement was to have conference rooms, and on the floor above - in the pavilion itself - there was going to be a restaurant, preferably one of Michelin-star quality, where ABN AMRO staff could dine with their guests. The walls and corridors could be used to house part of the bank’s impressive art collection. Those involved with the project felt the plans reflected the way a bank should look: classy, business-like, streamlined, professional.

The initial design reflected the way a bank should look: classy, business-like, streamlined, professional.

Rob Kuipers was working like a beaver to get the head office the highest possible sustainability certificate in the world: BREEAM's ‘Excellent’ certificate. He'd had all the windows covered with infra-red foil to stop the building from warming up too quickly and to save energy by reducing the need for air conditioning.

The head office also switched to sourcing its energy from wind turbines and bio-gas, cutting its CO2 emissions to a minimum, and the bank had implemented a range of waste-saving measures too. Kuipers was also working on the ABN AMRO branch office in Alkmaar, built in 1965, where the bank was working with The Green Quest sustainability collective to make the building completely energy neutral.

Like many other businesses and organisations, ABN AMRO is advancing further down the 'green' path, for it also sees the urgent need to tackle the climate problem and keep the planet habitable.

Sustainable ambitions

The project team at ABN AMRO looked at the plans for the pavilion and were not impressed. The team members were, in fact, amazed that these plans for an entirely new building hardly contained any sustainable elements at all. As they were then, the plans would actually result in a pavilion with a lower sustainability score than the head office itself.

The team members felt the ‘feel’ of the building was wrong. With the bank talking more and more about sustainability, wasn’t it time it did something tangible to reflect that?

The three project team members decided to try, together with Hans de Jong, to steer the work group in a more sustainable direction. In 2015, with an increasing number of people coming to appreciate the serious need to do something about climate change, the scarcity of raw materials and saving energy, a standard 'off-the-shelf' construction was no longer something you should be building.

Avoid any risks

As a result, the project team started to question the builders (BAM Bouw & Techniek had won the contract some months before), technical advisors and the architects, and went on doing so. All the parties had some experience of sustainable design and construction, but not on a scale that matched what the team at ABN AMRO had in mind. How was the energy supply going to be dealt with? Could it be done in a greener way? Why use this particular material? Is this the most economical and efficient solution? Isn’t there a more sustainable option?

The construction team was reluctant to start experimenting; they wanted to avoid any risks. And the designers responded by saying: Well, you wanted a pavilion that matches the bank’s needs and complements the head office, and that’s what we’ve designed. A totally sustainable building would end up looking totally different.

In addition to this, as the members of the work group said, these plans had already been approved, right up to board level. It was going to be difficult to change all that. Maybe we could do something like linking the cooling system up with the one in the head office? Or use a more efficient heating system?

A deep sigh was heard coming from Rob Kuipers.

In the meantime, Malu Hilverink was beginning to argue the case for sustainability with growing enthusiasm. Not only in terms of the construction itself, but also regarding the ultimate use of the pavilion. Couldn’t it be much more than just a conference centre and some hospitality facilities for the bank alone? Shouldn't it be a much more public space, one that inspires others to adopt a 'greener' approach to design and construction?

She organised a sustainability meeting to provide the entire team with some inspiration. She arranged for sustainable snacks to be served and gave an inspiring presentation about the importance of energy-saving construction, using raw materials from the right sources, the future of the planet, and the opportunities for a major bank like ABN AMRO to make a real impact with this pavilion.

During that meeting, a discussion arose about whether a grey-water system should be included, collecting rainwater to flush the toilets and water the garden around the pavilion. An expensive system, but one that would save a lot of clean drinking water. Yes, great, commented one of the technical advisors, but it’s also complicated and expensive. And, you know, drinking water is so cheap in the Netherlands, you don’t need a grey-water system like this at all. The three ABN AMRO project team members stared at one another. This wasn’t going to be easy.

##The train thundered on

It was now almost the summer of 2015. The atmosphere in the project team was tense. The builders at BAM and the designers at de Architekten Cie were getting more and more peeved by the flood of critical questions from the ABN AMRO team. They, in turn, were growing frustrated about the possibility of the bank missing out on the chance to execute a truly sustainable project. But the train thundered on all the same. The builders at BAM wanted to get on with the work, there were deadlines to be met, staff at the bank were in desperate need of places to meet...

Rob Kuipers, Rudolf Scholtens, Malu Hilverink and Hans de Jong held a meeting in the canteen at ABN AMRO’s offices at Hogehilweg in Amsterdam Zuidoost. What now? Continue down the same road? If we do, there'll be a conventional pavilion standing there soon. It'll look good, certainly, but it will also be a missed opportunity.

And the alternative? They didn’t have a precise idea in mind, but they knew that they needed some extra time. The four of them took a radical decision, all on their own. They were going to bring the process to a halt. Their aim: to switch to a totally sustainable construction project. The process wouldn't start again until a new design had been made and all the parties were prepared to commit to new, sustainable goals. Anyone not prepared to do that would no longer be involved in the project.

Hans de Jong walked back to his office and began to compose an e-mail.

Closing the circle

Residual value is what counts

It’s not clear who coined the term ‘circular economy’, but the underlying principles come from a movement that’s also referred to as ‘cradle to cradle’. Back in the late 1990s, the leading guru of this movement, American architect William McDonough, and German chemist Michael Braungart argued for a radically different approach to the use of raw and building materials.

The principle at the heart of the cradle to cradle philosophy is that the sources of many raw materials are not infinite, yet they are treated as if they are in traditional construction and design processes.

We take a raw material and then process it in some way that cannot be reversed, then we build or produce something with it. At the end of the lifetime of the building or product, we either demolish or dispose of it and the raw materials end up on a rubbish tip. All their value is lost.

If you want to build something according to the cradle to cradle philosophy, then you do it in such a way that all the materials left at the end - when the building is demolished - can be reused, and scarcely any waste is produced. “There’s no such thing as waste material” is a phrase often heard within this philosophy.

Regeneration

The circular economy takes these ideas further. It is founded on the principle of regeneration, of maintaining the value of raw materials as much as possible and continuously. In terms of building and product manufacture this basically means designing them from the very beginning in a way that the raw materials used - either sourced in the most sustainable way or, even better, already used elsewhere - still have the greatest possible residual value at the end of the building’s or product’s lifetime.

Those raw materials can then be used once again in a new building or product which, in turn, is designed as 'smartly' as possible. In this way, the circle remains unbroken and, in principle, the raw materials can go on being used indefinitely.

The circle remains unbroken and, in principle, raw materials can go on being used indefinitely

The principles of the circular economy have become increasingly popular in recent years. This is because they are in line with the move towards sustainability, socially-responsible enterprise and people, planet, profit. Some scenarios envisage a future economy in which humanity has the least possible impact on the environment, in which it uses natural resources and everything it takes from nature in such a way that everything possible is regenerated in non-exhaustive and non-polluting ways.

But the principles of the circular economy can also be applied in other fields. In commercial partnerships, for example, they mean parties no longer simply focus on their own profit at the expense of the other, but that they work together to achieve the best possible outcome with the least possible environmental impact or exhaustion of raw materials. For the labour market, they mean inclusivity and decent work for all. In this way, you can apply circular principles to every aspect of the economy.

Look, for example, at the way we deal with ownership. One well-known example comes from the architect Thomas Rau, who wondered in an edition of the Dutch TV programme Tegenlicht, entitled The end of ownership, whether our need for lighting necessarily means we need to own the lamps and light fittings that provide it. Light bulbs have a limited lifetime. That’s not because they are by nature particularly fragile, but because they are designed that way. The light bulb manufacturer does this to ensure that consumers have to go on buying the product.

Rau’s reasoning is that if you possess a product but place responsibility for the actual hardware with the manufacturer, then that manufacturer will ensure that its products have the longest possible lifetime. Replacing that product will cost the manufacturer money, not the consumer. Furthermore, it will design its products in such a way that they will be easy to repair and to disassemble.

One big circle

Circular principles are contagious. In recent years, more and more businesses and organisations have been joining the movement that ultimately wants the entire economy to become one big circle. One major beer brewer is already using the residue from its production processes to make bread, a clothing manufacturer is making jeans from plastic waste recovered from the sea, and a water company is filtering humic acid from water and using it as soil conditioner.

The government is also enthusiastic about circularity. In June 2016, the Social and Economic Council issued recommendations about making the Dutch economy circular. In September that same year Deputy Minister for Infrastructure and the Environment Sharon Dijksma and Economic Affairs Minister Henk Kamp presented their nationwide programme setting out plans to make the Dutch economy fully circular by 2050.

So, you want sustainability?

There was great confusion at the offices of de Architekten Cie on Amsterdam’s Keizersgracht when the e-mail from Hans de Jong appeared. ABN AMRO, a major client that the business had been working with for years, had suddenly put a major project on hold. Hans Hammink, the senior architect who had made the design for the pavilion on behalf of de Architekten Cie, was totally shocked. What did all this mean? Meanwhile, no one was answering the phone at ABN AMRO

The reaction in the bank’s higher echelons to the project team’s decision to call the construction work to a temporary halt was one of surprise. Mark van Rijt, , then the bank’s Managing Director Facility Management, had taken a fairly hands-off role in the building of the pavilion up to that point. Reading the e-mail from Hans de Jong, he realised that the project group clearly had objections, and he was eager to know more about the possible alternatives.

But Van Rijt also had to be realistic. Decisions like this have major consequences for a project of this size, in terms of both time as well as money. A blind and abrupt step into the sustainability 'maze' wasn’t necessarily a wise decision. After all, this pavilion wasn’t some crazy experiment in some obscure ABN AMRO laboratory, it was going to be a prominent feature in the Zuidas district. That wasn't something to be taken lightly. On top of that, the building work was already underway and the plans had been approved by all concerned months and months ago. Nonetheless, Van Rijt mailed Hans de Jong, saying that if the objections were really that serious, there would be room to discuss an alternative route. He wanted to know what they had in mind.

Experimental ideas

At roughly the same time something was beginning to stir inside architect Hans Hammink. More or less by coincidence, a student from the TU Delft (Delft University of Technology) - Luuk Graamans - was working on his graduation project at de Architekten Cie. His studies focused on circular construction and design. For his thesis, he was investigating ways in which buildings like the ABN AMRO pavilion could be made as circular as possible in terms of their design and construction.

Nice experimental ideas and ones which de Architekten Cie was hoping would help get it on the right track for the distant future.Hans Hammink, however, now realised that future might not be quite so distant any more, and these 'nice experimental ideas' could soon become a reality.

Hammink decided to shift gears, and quickly. He called Graamans and a group of staff from Cie and the TU Delft together. They broke their heads over the question of how they could take the existing plans for the pavilion - now already under construction - and remould them into a circular form.

In just two weeks they produced a booklet setting out their ideas. They hadn’t produced a new design at this stage, but instead described what the concept of circularity could mean for this pavilion and for the bank as well. As a real-estate financier the bank could not only show what circular construction means, but also gain experience with lease constructions as a replacement for ownership, including all the related financing and ownership issues. And, as Cie suggested in the booklet, that pavilion could provide a podium for circular initiatives to make society aware of their potential.

A 'circular' pavilion

When Hans de Jong's team at ABN AMRO put their phones back on two weeks after the ominous email, Hans Hammink got in touch straightaway. A couple of days later Cie presented the booklet at a meeting with the ABN AMRO team. You want sustainability? What do you think of this, a circular pavilion that's not only built according to sustainable principles, but will also be a living lab, a podium for these new construction and working principles?

It was bang on target. The people from ABN AMRO looked at one another. This is ambitious. This is innovative. This is precisely what we want. Sustainability as the sole guiding principle. They took the decision almost immediately, they were going to work together to develop this into a new design, and in doing so really come up with something to impress the management of ABN AMRO.

A pressure cooker

The period that followed is one that those involved describe as a pressure cooker. A new design was needed at speed. Everything possible about it had to adhere to circular principles. The bank, Cie, the TU Delft, construction company BAM (now relieved that things were on the move again) organised a series of brainstorm sessions that all followed one another at short intervals.

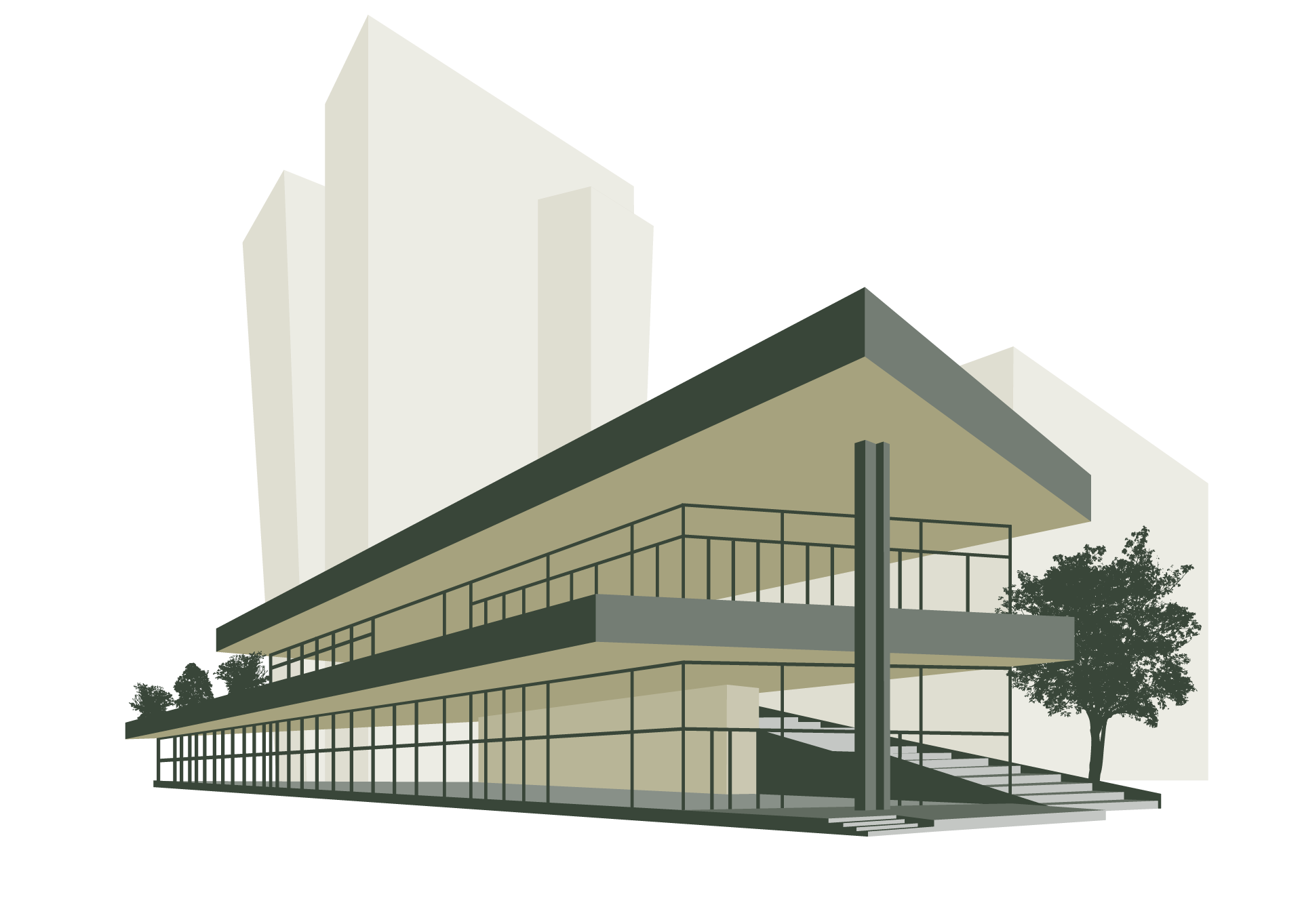

At this stage, there were a number of choices that couldn't or shouldn't be reversed. The concrete box that formed the foundations and where the meeting rooms were to be created was already in place. And the basic shape of the original design - an oblong pavilion with a large basement, a multi-functional and open ground floor, and a large roof garden with a cafe - was something everyone had been enthusiastic about. That all had to stay largely as it was.

But the changes that resulted from those brainstorm sessions and became a part of Hammink's new design were significant. This was mainly due to one of the key aspects of circularity. The new pavilion had to be one that, were the building ever to be demolished, could be disassembled as much as possible so that the construction materials could be used again elsewhere. This means turning the traditional building process on its head. It's no longer a matter of producing a design first and then looking for suitable materials, but of finding out what materials are suitable, have a low CO2 impact in terms of their production and transport, and how can they be used in the most circular way possible.

Wood instead of concrete

So, the concrete structure that was meant to support the building was dropped in the new design. A relatively large amount of CO2 is released in the production of concrete, and it's not something that can easily be recycled. In its place, large larch wood beams would be used and screwed together. Those beams are actually a fraction longer than they needed to be because this makes them easier to reuse. Simply saw off the parts of the beams where they were screwed together and you're left with wooden beams that can be used straightaway to support another building. The supplier also delivered the leftover parts of wood to the bank. They would be used later to make large parts of the restaurant's interior.

The wood also changed the pavilion's image. Instead of a streamlined bank pavilion with marble facades, it became a warm but robust wooden structure. Many features were dropped on the inside of the building too, in accordance with the 'reduce' principle. There are no fitted ceilings and the pipes and cable ducts have not been concealed.

During the brainstorm sessions, the architect had occasional doubts about whether the new design wouldn't be too 'rugged' for the bankers. At a certain point, he suggested painting the beams white to create a more refined look. But that would have involved unnecessary paint and, moreover, make it more difficult to reuse the beams.

Unknown territory

There were numerous choices to be made. What kind of panels should be used for the facade? What about the floors? Could we use geothermal heat exchangers? Solar panels, yes, of course, but what kind and where do we put them? And what about the air conditioning? It became clearer during the brainstorm sessions that the majority of those choices would have to be made during the building process itself. It became a matter of building and designing at the same time, because circular construction was unknown territory for everyone concerned. Yes, the principles were clear: minimal single use of raw materials, as energy-neutral as possible, everything designed to be disassembled later. But how do you actually achieve that in practice?

The principles were clear: minimal single use of raw materials, as energy-neutral as possible, everything designed to be disassembled later. But how do you actually achieve that in practice?

After more than four weeks of brainstorming, the ABN AMRO project team and de Architekten Cie organised a meeting for all involved at restaurant Baut, then housed in the former Citroën garage on Amsterdam's Olympiaplein. The choice of a pop-up-restaurant was deliberate. The kitchen, the interior, everything about the restaurant was temporary and could be taken apart and easily used somewhere else.

The project members were tense. Cie was about to unveil its plans for the new pavilion in front of a larger audience for the first time. The people at the meeting were going to pass judgment on the pavilion team. Had they totally lost the plot, or been transformed into visionaries?

The judgment was positive. Everyone felt intuitively that this was the right way to go, that this new pavilion was simply right. The atmosphere was even euphoric: “We're going to do it, we're going to make a difference.” The circular philosophy is infectious. This pavilion could be so much more than just a showcase for sustainable construction.

Yet, in the backs of their minds, the project members were aware that the bank's management wasn't on board yet. The team members realised they would have to come up with a good story to get the green light from them, because there were all kinds of practical reasons why people might simply want to proceed with the original plans. That story was ready. It included plenty of sound principles, good intentions and a fine but rough design for a new building, but other than that, there wasn't much of practical use on the table at all.

There was no 'how to construct a circular building' manual back in 2015. But this in itself turned out to be an incredibly strong argument for doing just that all the same.

We want to change the world

One day in October 2015 - while construction of the pavilion was still at standstill - Malu Hilverink, Rudolf Scholtens and Pi de Bruijn presented the new plans to each of the ABN AMRO managers, one by one, who had a say over the bank’s real estate. Their pitch was that this presented the ultimate opportunity for the bank to make an impact, to change the world a little.

The team members argued that a bank could, of course, easily decide to create the most sustainable building in the world. Just take a large pile of cash, choose a super-sustainable firm of architects, use the most modern energy-production and smart-building techniques, and create a showcase. Then stand back and say, look at all the things that are possible these days and look at what we've done.

That in itself would be valuable and inspirational. But would a process like that actually be internalised if handled that way? Would it not be more valuable to go through a learning process in a fully transparent manner, to show your vulnerability and to try, as a relatively traditional institution, to demonstrate that everyone can achieve and afford circularity? That would be something not only the bank could learn a lot from, but also other organisations with as yet little experience of circularity.

No standards

Banks, by nature, do not feel comfortable about making themselves vulnerable, and ABN AMRO has a moderate risk profile. The circular economy is, however, such a new concept that it still has no established benchmarks or standards, or off-the-shelf solutions.

The new plans for the pavilion required a leap of faith from the bank. It was going to be saying, “We don't know exactly how to do this either, this circular construction, but we believe in the principles behind it.”

And we and our partners not only want to learn from this process and help each other move towards circularity, but also share what we learn with our clients. No copyright here – in fact, everyone will have a right to copy. Because that's the only way to get everyone involved in the circular transition. Not just the forward-thinking vanguard, but the large, well-established parties as well.

That message was heard by the heads of the bank. Coincidentally, Mark van Rijt had a book about circularity lying on his bedside table at the time, and saw great potential in its principles. Yes, he could also see some obstacles - particularly in terms of time and money - but the group's enthusiasm and idealism were infectious. He believed their vision was crystal clear and was impressed by their presentation.

A major player on the real estate market

And something else played a role. ABN AMRO is a major player and has a major impact on the construction and real estate market. The bank's balance sheet includes 185 billion euros in outstanding loans for homes and construction projects. Sustainability and circularity are themes which the construction and real estate world will inevitably have to address in the decades to come. So, wouldn't it be the right thing for the bank to set an example and use its own hands-on experience to show others how to do that? And to use its influence to challenge partners and suppliers to start working in the most circular way possible?

There was also an element of urgency from a business point of view. Not only is it likely that all office buildings in the Netherlands will need to have at least a grade C energy certificate by 2023, but the ultimate goal is for the Dutch economy to be fully circular by 2050.This means that existing buildings will also have to meet increasingly stringent demands. If that doesn't happen, then they will by definition lose value, and that would be bad news for the bank's real estate portfolio.

Despite the obstacles, Van Rijt realised this was something the bank simply had to do. He wasn't able to foresee all the consequences, and it was going to be something of a leap in the dark, but he felt intuitively that this was the right way to go. Now it was up to him to ensure the project could become a practical possibility and yet stick to the planning.

This meant, as he said, that the right balance had to be found during the rest of the building process between time, money, functionality and circularity. If the bank was going to do this, then the things it learned in the process were also going to have to be achievable and affordable for others. In short, extremes were to be avoided.

The project members, relieved and overjoyed that they could proceed, agreed with Van Rijt.

In the days that followed, Van Rijt spoke to each member of the board individually. They, too, saw the opportunities that the new course set out for the pavilion would offer. The work group got a definitive green light. ABN AMRO was on course to build a circular pavilion.

Circular dilemmas

We drove them mad sometimes

When Nick Jaring first heard about the ABN AMRO pavilion and the circular ambitions, he was a touch sceptical. Sustainability was fine, as a building engineer and project leader with BAM he had the requisite knowledge about that. But circularity? That was pretty abstract. He began to search the internet, talk to the people involved, and with BAM's special sustainability team, because - in July 2016 - he became BAM's project leader for the construction of the new pavilion.

Once the go-ahead had been given by the bank's board, things started to move very fast. Everyone involved in the project knew they were going to be doing things completely differently from then on. For BAM, too, that took some getting used to. Not only did the bank want to re-negotiate with the contractor once again - the earlier contract had been cancelled - but the bank also said that, as the client, it wanted to be much more directly involved in the project than was normally the case.

Circular questions

Each potential partner - from designer and advisor to suppliers and installers - was presented with a series of ‘circular questions’. Where exactly do the raw materials for your product or design come from? How do you view circularity? How can you adapt your product to make it easy to disassemble later on? How can you create an impact in your own supply chain?

Everyone was challenged to think outside the box. The construction team then chose the parties which had really thought about the principles and hadn't simply viewed sustainability and circularity as part of their sales pitch.

(in Dutch)

The people from ABN AMRO and the architect found themselves having to explain it all time and time again. And they went on asking critical questions. It was, as Nick Jaring called it, 'a challenging process'.

Unconventional choices

Together with the TU Delft, the parties came up with a number of remarkable systems, including the pavilion's system of horizontal and vertical geothermal heat exchangers that helps to reduces 'normal' energy usage. The vertical ones comprise a series of nine boreholes, some 80 metres deep, and use geothermal energy to heat and cool the building.

So-called PCMs - phase changing materials - were used throughout the floor and ceilings in the ground floor, the same as ABN AMRO had already installed in its Alkmaar office. PCMs are like the elements in a cool box and contain a saline solution which either solidifies or melts depending on the temperature settings. They work like a kind of thermal battery. When a space reaches the desired temperature - 20 degrees, for example - the solution melts and produces a cooling effect. When the temperature drops - when thermally cooled water from the geothermal heat exchangers is pumped over the PCMs, for instance - then the solution solidifies and 're-charges the battery'. A thermal buffer like this means the temperature in the building can be controlled with a minimum use of energy.

Circular construction also means thinking about waste flows and only using and installing features which are really necessary. In this case, there was a question about whether the concrete basement should have a floor. ABN AMRO felt it shouldn't unless there was a structural or some other practical reason to do so. In the end, the concrete itself was simply sanded and polished – nothing more than that.

The floor of the underground concrete structure was going to suffer a little during the rest of the building process, and normally the contractor would have covered it later with floor protector, a kind of protective layer made of paper. But with 1,600 m2 to be covered, that would have created quite a lot of waste, so BAM and ABN AMRO decided against it. This also meant that the basement floor looked a bit 'used' when the building was completed (to limit this 'used' look the work platforms were fitted with special white tires during the building work).

Screw, bolt, click, clamp

The construction firm also faced stringent requirements. If a building has to be easy to disassemble, then 'wet' bonding agents like glue, kit and polyurethane foam are a no-no. Instead, everything has to be screwed, bolted, clicked or clamped together wherever possible.

Similarly, all the work is going to be ‘visible’. Traditionally, a carpenter may sometimes use a section of bare wall like a scrap of paper to work out some measurement or calculation. But this building was going to have a rugged, minimalist finish. Anything you saw during the building process was going to be seen later by the people using it. So, BAM issued an edict to all its workers, “No scrawling on the walls, please”.

Another idea that came from BAM - also illustrating how changes were made throughout the building process - was sparked by the wooden floors on the ground floor and first floor. To insulate them against impact sound some kind of bulk material had to be used. One early design envisaged the use of sand. After all, sand can easily be reused. But laying a smooth, perfectly flat layer of sand in a place full of construction workers would be asking for problems. So, BAM suggested using paving stones. The mathematicians got to work and said it was possible.

A batch of used paving stones was delivered and the builders were free to trample all over the floors at will.

Another choice with environmental benefits related to the fact that the whole building would be using direct current (DC). Solar panels produce DC, but standard electricity networks use alternate current (AC). Inverters are normally used to convert solar power to AC so it can be fed into the network. Yet many types of equipment - laptops, smartphones, etc., - run on direct current. Hence the need for an adapter to charge them. Rob Kuipers. realised, with the 'reduce' principle in mind, that you could do without the inverters and adapters and connect that kind of equipment directly to the solar-power supply. That would reduce the need for more equipment and materials - including raw materials - and reduce the amount of energy lost through the use of inverters. As a result, the building's LED lighting, for example, now runs on DC, and laptops and mobile phones can be charged without adapters.

Urban mining

The ‘reuse’ principle brought the project team into contact with Amsterdam-based business New Horizon. They call themselves ‘urban miners’ and recover - or 'harvest' - valuable residual and raw materials from empty buildings on the demolition list. New Horizon went on to supply used fire-hose reels and cable ducts for the new pavilion, and also the paving stones that were used for the floors.

(in Dutch)

On the ground floor, a collection of hardwood taken from a former monastery and the bar of Dutch football club Top Oss was used to make the floor. The partition walls for the basement conference rooms came from a building in Hilversum that once belonged to Philips. They didn't quite fit, so some extra partitions were used in places to complete the rooms. In this case, ‘reuse’ took precedence over aesthetics, although everyone thinks the finished walls look great. And it all makes a compelling story.

In line with Thomas Rau's vision, ABN AMRO decided not to buy the lift for the pavilion, but rent it from the manufacturer, Mitsubishi. The bank now pays for it on the basis of each 'vertical movement'. And although the original plans included two lifts, the bank and architects eventually decided that one would be enough. After all, people can use the stairs.

This building didn't have to be as beautiful as possible, but as good as possible

For architect Hans Hammink the project continued to pose dilemmas at times. As he says himself, he had to develop a new aesthetic. In 'normal' design and building processes, things are sometimes dropped because, as he says, 'they aren't acceptable from an aesthetic point of view'. But the balance was weighted differently with the ABN AMRO pavilion. This building didn't have to be as beautiful as possible, but as good as possible.

However, Hammink says, make no mistake, it's still a wonderful building, even though it's not at all the same as the one envisaged in the initial design.

A meeting place

As the contours of the building began to emerge on the square at the beginning of 2016, and a growing number of people were being shown around the place - clients, real estate partners, other banks, local residents, schools and other interested parties - the project team began to think about what the inside of the pavilion itself was going to be used for. The meeting at the former Citroën garage had sparked the imaginations of many people.

Malu Hilverink took on the task of ensuring that what happened inside the finished pavilion would also be circular. The original plans to create meeting space and catering facilities were, of course, still in place. But what would this circular approach mean in terms of its other uses?

The pavilion needed its own general manager to handle this and its day-to-day operations. This person, working together with a team, would have to ensure that the pavilion's programming did justice to the circular principles which ABN AMRO wanted to help promote. Furthermore, that team would need to see to it that the pavilion made enough money and created sufficient new business initiatives to make it a going concern. Circularity and sustainability are important, but - as all the bank's representatives on this project knew – the pavilion wasn't meant to run at a loss.

A new business

When Merijn van den Bergh heard about the plans for a new pavilion, something in him stirred. At that time, he was ABN AMRO's Manager of Corporate Buildings, but he'd been keen to take on a more entrepreneurial role for some time. The more he heard about the pavilion, the more enthusiastic he became about the ideas and the energy the project was generating.

And he sensed the challenge: how could you ensure that a project like this also became a commercial success? He contacted Malu Hilverink and, when they were discussing the building one day, the penny suddenly dropped. Perhaps Van den Bergh should be the new general manager.

Van den Bergh couldn't get to sleep that evening. This was exactly the kind of thing he wanted. A business combining hospitality and sustainability, a meaningful job, combining substance and commerce. The next day he put himself forward as a candidate for the position, and a few interviews later, the decision was taken – Merijn van den Bergh was to be the general manager of Circl, the name chosen for the new pavilion. The main objective of the new pavilion was also defined: to facilitate a rapid transition to a circular economy.

Roles

The pavilion could play all kinds of roles in that regard, just as de Architekten Cie had already suggested. It was obvious that it was going to stand as an example of circular construction. It could be a living lab where circular ideas would be tested. But, above all, it would be a meeting place – for the bank's clients who want to do more with circularity, and for other businesses and organisations. In other words, for anyone and everyone who wants to do 'something' with or about circularity.

This could be achieved by organising meetings, debates, competitions, workshops and open stages, all focussing on the themes of people, planet and profit. Van den Bergh and Hilverink approached Pakhuis de Zwijger, a cultural and social centre in Amsterdam which hosts events on the theme of urban sustainability. Together they began to brainstorm about the future of the pavilion.

(in Dutch)

All kinds of ideas started to surface. The pavilion might offer an open stage for young artists, host dinners under the theme of 'connecting' – where, for example, bankers, refugees and students could get to know one another. It could also act as a kind of market place, bringing together businesses in the Zuidas area and other social organisations.

The team members and other people at ABN AMRO began to come up with even more ideas: a sustainability boot camp for children, a design studio for circular products, a weekly debate and panel discussion about circularity, a cookery workshop focussing on sustainable and circular cuisine, a social accelerator where staff from the bank present potential solutions for social problems, an innovation challenge for sustainable initiatives, etc.

School pupils

The bank also established contact with a local primary school, the Merkelbach School. Pupils from the school were invited to pay a visit and asked to think up all kinds of activities that might be used to propagate the pavilion's circular principles. They were also asked to make a film about circularity that would be shown in the pavilion itself.

News of the radical changes in the pavilion project also spread through the bank itself, generating enthusiasm among a growing number of people. Retired ABN AMRO staff started volunteering to act as tour guides at the building once it was completed. A campaign to collect old jeans was launched at the head office. The insulation company, VRK, was going to fiberise the jeans to make sound-proofing material for the ceilings. At the beginning of 2017, ABN AMRO's new Chairman of the Board, Kees van Dijkhuizen, chose to be filmed in and around the pavilion - still under construction - for a vlog about the bank's latest Annual Report.

The momentum was there, and ideas and plans mushroomed. Circularity is a major source of inspiration, as Van den Bergh noticed, yet he still faced considerable headaches regarding the future exploitation of the pavilion. He believed that with the right kind of exciting and attractive programming, the pavilion would sell itself easily on working days when the square is a hive of activity.

(in Dutch)

The question really bothering him was whether the pavilion would also be attractive enough at other times. The principles of circularity are clear and unambiguous, but if you focus too much on the circular narrative alone, you run the risk of putting people off. Van den Bergh felt it shouldn't be too extreme. The pavilion was also supposed to generate new business for the bank - new clients, new forms of partnership and cooperation – and that had to be a success.

Dilemmas

Dilemmas like this kept cropping up regularly during the rest of the building process. Mark van Rijt went on repeating that the project had to stick to the plans in terms of time, money, functionality and circularity. Ideas like including a system in Circl to store solar power might be good ones, but they had to be viable. If it was going to cost 450,000 euros to develop a system like that when you could purchase one from Tesla for a 'mere' 150,000 euros, then the choice was clear. And if you want to make an impact, then the solutions you come up with need to be achievable for others too. With regard to the pavilion's power supply, an even better solution would be to wait until Circl had been open for a few months. Then you would be in a better position to assess what kind of power storage, if any, was actually needed. Here again, like almost everything else with Circl, things went step by step.

Circular eating and drinking

The pavilion faced similar dilemmas with respect to hospitality. The hospitality provided at a circular pavilion ought to be based on the same principles, but the pavilion's hospitality operation was going to be sizeable. Not only would the ABN AMRO meetings require what the Dutch call 'banqueting' - coffee, lunches, refreshments - on an almost daily basis, the pavilion was also going to have a ground-floor restaurant for the general public, plus a bar offering less lavish meals on the first floor.

In the spring of 2016, ABN AMRO launched a tendering process, presenting its new pavilion and asking organisations to come up with challenging concepts that matched the bank's circular ambitions.

One of the parties that responded soon and became the big favourite - and actually got the contract in the end - was Vermaat, the hospitality company that also runs the new RIJKS restaurant at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum. The company has a reputation for developing made-to-measure concepts for all kinds of clients. The plans set out in Vermaat's pitch were good, but the thing that decided it for the bank was how Vermaat presented itself as an organisation that is willing and eager to learn.

New terrain

Like many other businesses in the hospitality sector, Vermaat was already working on the theme of sustainability in various ways, but - as the company openly admitted - for them, too, circularity was relatively new terrain. But it was exactly the choices and decisions that Vermaat would face in the process that it was keen to learn from. It was also prepared to share what it learned, and to challenge its own partners. With almost 300 locations and more than 3,000 staff, the company's potential impact is great. And there would be plenty of choices to be made in developing Circl's hospitality concept. On a really busy day, Vermaat will have to cope with around 300 people meeting downstairs and needing breakfast, coffee, tea and lunch. The ground-floor restaurant has room for 100 to 150 people, while the bar on the roof can accommodate about 80.

One of the questions to be answered concerned energy. ABN AMRO wanted a low-energy pavilion, so Vermaat was initially offered a 35-kilowatt supply. A 'normal' restaurant of this size needs a minimum of 200 kilowatts. As a result, in one of the initial plans, Vermaat proposed using wood ovens, a constant and relatively economical form of energy that would also create a more 'primitive' kind of atmosphere and not require any electricity.

But the bank rejected the idea. The heat escaping from the ovens would upset the pavilion's fine-tuned climate control system. Vermaat would have to manage with the available energy, although the bank later increased the capacity to 100 kilowatts – still only half of what would normally be required. Vermaat proved to be flexible and creative. If this meant no fried snacks because the fryers used too much electricity, then they wouldn't serve fried snacks with people's drinks. Instead there would be sourdough snacks, for instance, or roasted aubergine skewers served with a dip sauce.

Thinking outside the box

Like all the other partners, Vermaat continued to think outside the box. How were they going to take orders in the restaurant? Perhaps they should use those handheld ordering devices which use very little energy and only need to be recharged once a day. And receipt printers, would they be needed? Or are guests these days ready to accept a receipt sent by email? And could the ingredients and other supplies not simply be delivered by just one lorry?

Just as ABN AMRO was asking its suppliers questions, Vermaat also began to challenge its partners, and the circularity theme trickled down the entire supply chain. The company found a Belgian supplier that makes work clothes in a circular way. But wouldn't it be more interesting and sustainable to establish a new supply chain with a local partner? Or, wait a moment, would they need company uniforms at all? Wouldn't an apron be enough? The staff could wear them over their own clothes.

When it came to recruiting staff, Vermaat also followed the inclusive principles of circularity. It was keen to work with people who traditionally have poor opportunities on the labour market, and concluded an agreement with a social workplace to bring them on board.

The newly-appointed head chef, Rudolf Brand, wanted to use seasonal, locally-sourced ingredients for the menu as much as possible. And the transparency aspect of circularity was also going to be applied to the kitchen where he'd be doing the cooking. It was going to be an open kitchen and there'd be an illuminated wall full of jars and pots containing all kinds of bottled, fermented, pickled, and other produce.

Banquetting circular style

When Vermaat started to build the kitchen, at the beginning of June 2017, the basement was already open for meetings and conferences. That meant the banqueting service also started. Everything was brought over from the head office, but Vermaat didn't serve the traditional kind of Dutch business lunch - trays of sandwiches, jugs of milk, and a load of leftover food and waste at the end. Instead, it created a large buffet in the central hall of the basement. A place where people could connect with one another while enjoying a fine meal.

Vermaat also want to organise the way it purchased ingredients and produce in such a way that any 'leftovers' could simply be taken back to the kitchen to be used for the restaurant. Reduce, reuse, and work towards ‘zero waste’.

But alongside all its circular plans Vermaat also had to consider its 'normal business guests'. They might not be particularly interested in circularity but simply want to enjoy good food and drink with their fellow guests. In that context, a good background story would be a plus, not the key. In the long run, Vermaat also wanted this to be a commercial success, so all those circular aspects couldn't come at the expense of quality. Moreover, a successful commercial concept was exactly what was needed to create more space for new circular developments and fund the necessary investments.

A 'green' garden

The square in front of ABN AMRO's head office – that's where this all began. That's why the entrance to the bank's headquarters had been an integral part of the very first sketches for the pavilion. One thing was certain: this square - largely paved and surfaced, with taxis coming and going - had to be changed.

During the initial design phase in 2013, de Architekten Cie worked with a landscape architect on a number of draft plans which complemented the original business-like image of the pavilion. When ABN AMRO made the switch to a circular pavilion in the latter part of 2015, however, the collaboration with the landscape architect began to get more difficult.

At the end of 2015, Donkergroen came into the picture. Donkergroen is a large landscape-gardening company that had previously handled the landscaping and vegetation around the ABN AMRO offices on Foppingadreef in Amsterdam Zuidoost. Like all potential partners for the pavilion, Donkergroen was invited by ABN AMRO to come up with a design, but above all challenged to think about circularity and the role it could play in the firm's own supply chain.

A place to relax

Elwin de Vink, chief designer at Donkergroen, thought long and hard. Donkergroen had already worked with sustainable principles for the Foppingadreef project, but this was something quite different. The bank's requirements were considerable. There was to be a garden where the bank's own staff, and also passers-by and locals, could relax, with enough space left for taxis and goods vehicles.

The fire service - and the window cleaners - had to be able to get to the head office. The Donkergroen team came up with a design in which, all in all, 90 percent of the new square would still be surfaced. That was not the intention.

Then, as De Vink recalls, he tried a little trick. Instead of producing a solid, highly-detailed plan, he and his team made a number of rough, overall views of how it could look. The garden would become a kind of green oasis, with floating elements, bridges, decking, etc., yet with enough space left over for the fire service.

The pavilion would have a 'green wall' full of plants, flanking the roof garden. The green area would cover a strip connecting the pavilion to the head office. Donkergroen presented its draft plans to Mark van Rijt and Rudolf Scholtens, but made one clear proviso: a lot would depend on the materials they were able to find and use. Hence the fact that they hadn't come up with a detailed and definitive design. Nothing's certain, Donkergroen noted, but they were keen to go on this journey of discovery, partly because they were eager to find out what impact they could have in their own supply chain.

This appealed to the people at ABN AMRO, and Donkergroen got the go-ahead. The floating bridges were soon dropped – they weren’t very practical for people wearing high heels. But, along the way, all kinds of ingenious circular ideas would be reviewed.

Donkergroen learned through the grapevine that a massive load of Belgian cobblestone was going to be up for grabs. These large stones had already been in service for around a thousand years. Sawn into shape, the stones would make a perfect surface for the area around the pavilion, and if the square is dug up or removed later, the stones will have hardly worn down at all and could be reused immediately.

Meccano

The landscape company also thought about the material for the plant and tree containers. They used Corten steel, which corrodes to a limited extent, but then stops. However, if you weld steel components, you can't reuse them very easily; the only option is to melt them down. So they came up with a new idea: the containers would be made from individual sections.

The various sections are linked together by hinges fitted with pins made from recycled plastic. They came in different sizes, bent in different angles, and looked very much like a large collection of Meccano parts. If the ABN AMRO garden ever needs a facelift or is replaced, they can be taken apart and reused in all kinds of different combinations.

Some solutions were born out of pure necessity. The square lies over the roof of the underground car park and that can support a maximum weight of 1,500 kilo. Donkergroen could have laid sand to fill the gap between the car park and the street above, but that would be too heavy. Polystyrene foam had been used previously – but that's made from oil.

After a prolonged search, Donkergroen found an alternative: foam glass, a waste product from the glass production process. It's as light as polystyrene foam, but a more natural product and easy to reuse. Donkergroen came up with even more ingenious ideas. A column with solar panels in the garden where people can charge their phones, an insect hotel, vegetation to attract birds, butterflies and insects that live in an urban area like Zuidas, and to provide a totally different picture as the seasons change. The plants - all native to the area - came from an organic grower in Wageningen.

De Vink says this project's impact on Donkergroen has been great. By being forced to think about circularity and ask questions at every stage and about each element, the business has started to look at its own operations more closely. And it's formulated a new mission for itself. Donkergroen aims to be a completely circular business by 2035. That's exactly the kind of thing the bank was hoping for.

Connecting people

September 2017. Things moved quickly in the final weeks before BAM handed the building over to ABN AMRO. Circl is here – the pavilion is finished. The final element in the Berlage axis has been put in place.

But is that really so? Is the project really finished? Does a circle ever have an end?

What began as a plan for some extra conference rooms and hospitality facilities for ABN AMRO's staff has ultimately become a meeting place open to all, with one sole objective: to speed up the transition to a circular economy.

How? By demonstrating how you can build in a circular way, by inspiring others, by setting challenges, by connecting people. But also by not avoiding difficult decisions and choices. And by continuously asking the question: what's the best way to create the maximum possible sustainable impact?

It sounds good, but it's not something that just happens by itself. As this story shows, building according to principles which are still totally unknown to many is an enormous challenge. Nothing is certain or a given. The likelihood of making mistakes is great.

However, everyone involved in this project - from BAM to Vermaat, from New Horizon to Donkergroen - says that despite the setbacks and problems, this project has brought them so much more than just a great assignment. Almost all the parties involved have learned to look at their own business and way of working in a different way. And almost everyone has, in their own way, been inspired to do business in a different and sustainable manner, and to challenge their partners to do the same. This means that, whatever else, a small part of Circl's objective has already been achieved.

The development of Circl has also demonstrated that you need visionaries, headstrong individuals who aren't afraid to go against the grain. People who know that you can only bring about real transformation by accepting the challenge. Who have vision, want to inspire and persuade others and, in turn, are prepared to be inspired and persuaded. And who dare to take a leap in the dark and gain the support and confidence of others to do that.

Circl is here now – it’s a new hotspot for circular ideas and inspiration. But Circl is not finished - in fact, this is just the beginning. The transition to a circular economy has only just begun. Circl hopes to play a role in this process, because it believes in the new, circular world. Together with the neighbourhood, businesses, NGOs, organisations and the public - anyone who wants to get involved - Circl will be taking new steps towards a sustainable society every day.

We look forward to seeing you at Circl.

This article was published in September 2017

gepubliceerd

on the occasion of the opening of Circl.